Enlightenment

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 2008

INTRODUCTION by A.N. Wilson

THE MARBLE INDEX

Hugh Buchanan’s paintings do not merely depict, they inhabit an architecture. You feel yourself in the rooms and houses which he has, over thirty years so incomparably evoked. You feel yourself inside, not merely particular spaces, but in those spaces as first conceived by the great architects who designed them. In his work of twenty years ago, these effects were sometimes achieved by paintings combining observation with imagination and by the loosening of architectural detail into dream – like spaces. Later , he came more and more to concentrate upon actual evocations of place.

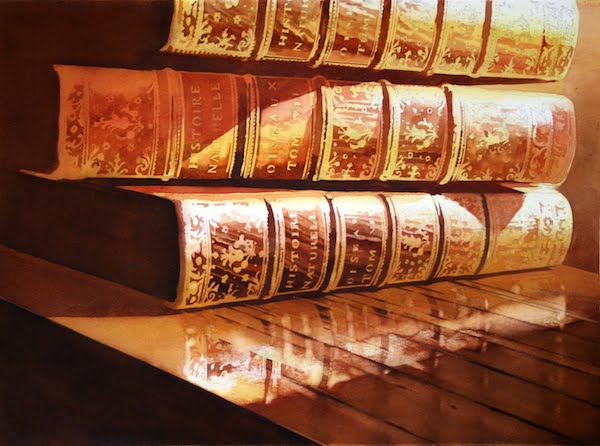

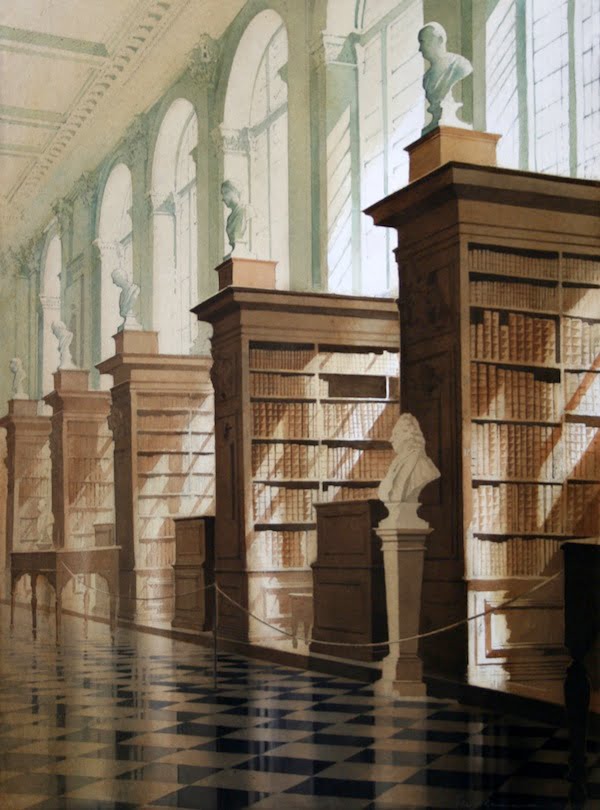

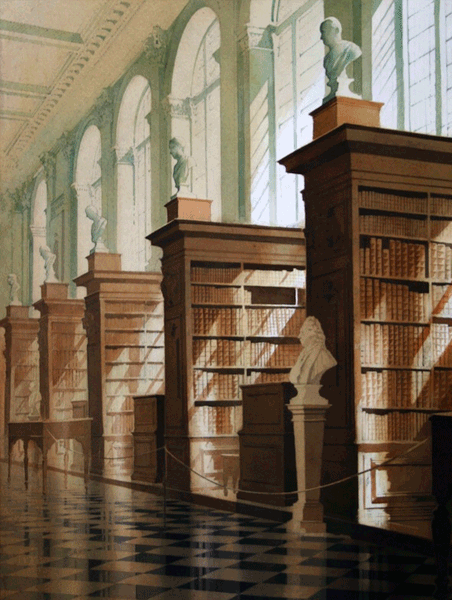

In many of the great houses and palaces he has painted, there have been libraries. The present exhibition concentrates upon a new departure for him. He paints the book in situ, with results which are extraordinary. We find ourselves in the library. And as in life, so in these pictures, we are sometimes close up to the mouldering, dried out leather of the bindings- as in the truly massive volumes of the vies des peintres at Eastnor Castle; or our eyes take in the great architectural vistas which have been created for the life of the mind – as in our glimpse up the almost endless shelves of the V&A Art Library, or in the cool perfection of the Codrington at All Souls college, Oxford or Trinity College Cambridge

Not only has the subject matter focused on one particular theme. The breathtaking size of the works is emblematic of their vast imaginative scope. There has been a distinct change in technique. Brilliant as his earlier work is these are surely his finest. The huge planes of wash with which he evokes folio volumes, or splashes of light coming through library windows, on to chairs or marble floors, have the plainness and truth of Cotman at his simplest and starkest. The shimmer of luminous detail, catching one small notebook at Holkham, one little bit of morocco binding, has the exactitude of expression and the exuberant love of life with which we might associate William Nicholson. We truly feel in these Buchanan book pictures that we are in the presence not just of a master technician ( and what a technique! What courage, to undertake the huger of these exhibits with the ever-risky watercolour medium!), but also of an artist at the very peak of his prime.

We also surely feel that these paintings are doing much more than just illustrating one place or another. These are works of art with a distinct subject. When he was at St Johns College Cambridge, Wordsworth, from his college rooms, could just see inside the ante-chapel of Trinity next door, and the statue which stood there-

Of Newton with his prism, and silent face

The marble index of a mind for ever

Voyaging through strange seas of Thought alone

Many who see Hugh Buchanan’s faithful pictures of the Library at Newton college, and the busts of such great classicists as Bentley, will recall Wordsworth’s lines. They apply as closely to what we do when reading, as when we look at an attentive artist at work. We see the mind of the artist, or scientist, or author, Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone. But by an extraordinary alchemy of art, we are able either to eavesdrop upon their inner dialogue, or even to find ourselves addressed, and met, by it. This is what these watercolours do. They depict, with preternatural skill, not merely what libraries look like but what they are for. They are not simply paintings of the outside of books, as they first appear. They are suggestive of the reasons the books have been written, and the libraries built to house them.

A.N. WILSON 2008

REVIEWS

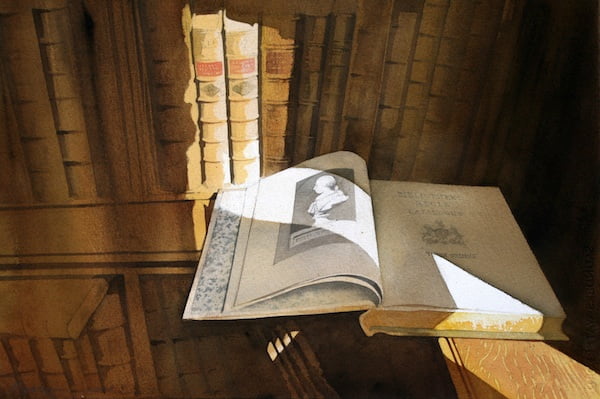

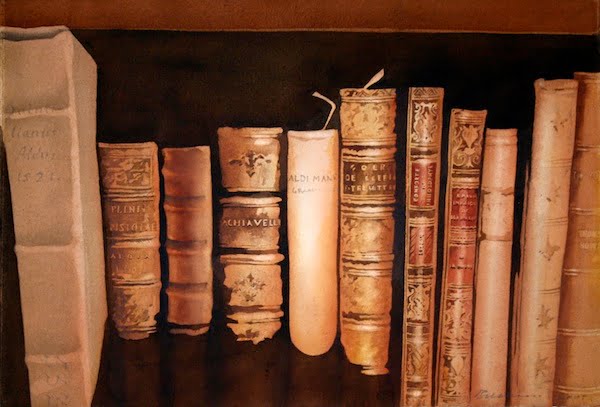

Here in contrast to his previous exhibitions, the architectural interiors for which he is best known and admired are upstaged by innovative paintings of books, removed from the shelves, liberated from their library surroundings, and brought into focus as objects in their own right, viewed from unusual perspectives and dramatically lit – or hardly at all, like the two volumes on a library table at Holkham.

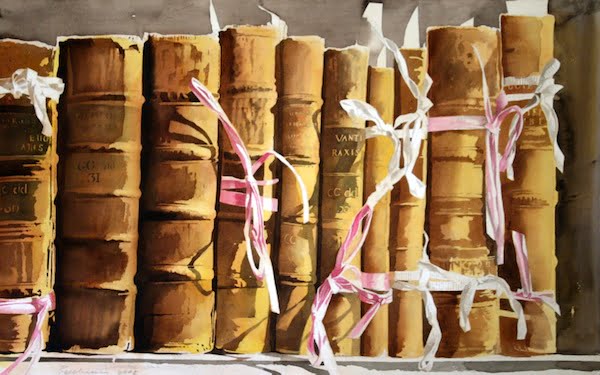

Parallels can be drawn with the surreal paintings of isolated, unoccupied chairs that appeared in an earlier exhibition. The suggestive human element of chairs is obviously lacking here, except perhaps for the hefty tomes with broken spines, held together by fluttering pink and white tapes in Trinity College Dublin, but books – like bricks give scope for more stupendous and arresting compositions. I was bowled over by a large close-up of brightly lit volumes from the library at Eastnor castle, identified by their gilt-lettered spine labels as Vies et Oeuvres des Peintres ( an appropriate choice for an artist), precariously balanced on an ambiguous surface and set against a mysterious black background.

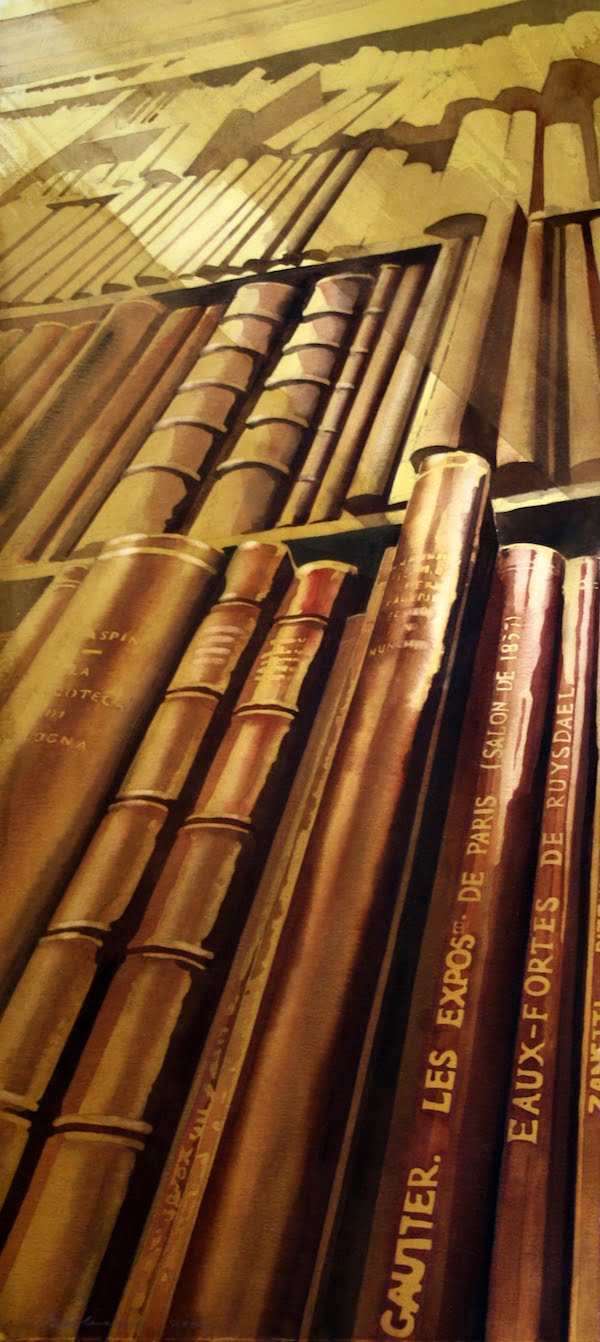

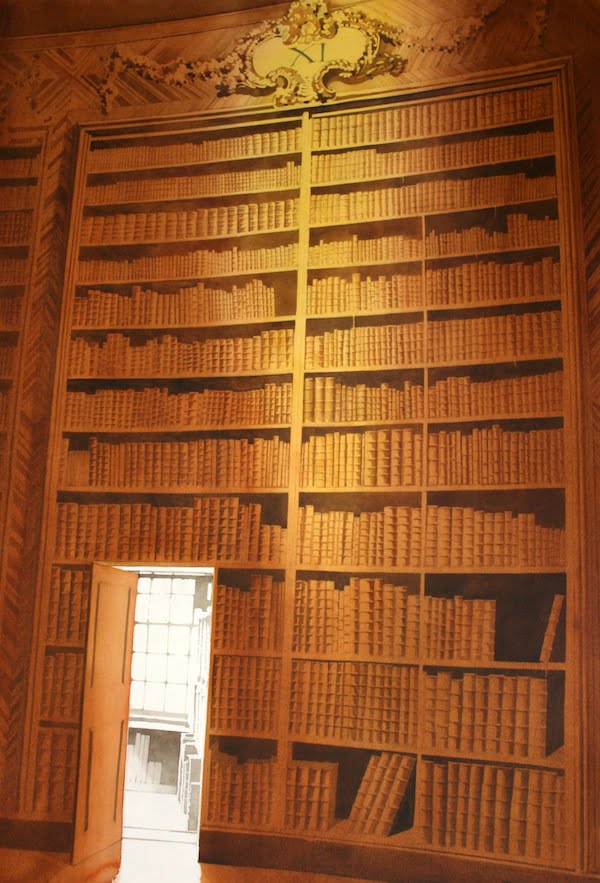

Totally different but equally staggering are two vast watercolours – 102 and 152 cm tall – each entirely devoted to a wall of books: one a vertiginous view of a tower of giant folios seen from below in the National Art Library of the V&A; the other a monumental bay in the baroque Prunksaal of the imperial library of the Hofburg in Vienna, bathed in mellow golden light, with the bindings of the inlaid wood surrounds all painted in translucent shades of brown, interrupted by a jib door opening to the bleached white light of an outer room. Although this iteruption gives scale and depth to the composition , the marvel to my mind is Buchanan’s ability to achieve so much variety and interest on such a large scale, with such a limited palette and without the help of furniture or figures.

A bold and masterly manipulation of light and shadow is the principal animator and one of the most distinctive features of Buchanan’s watercolours. Shafts of light are deployed not only to bring out the lustre of the gilt-tooled spines of the volumes of L’Histoire Naturelle piled up at Eastnor castle and to represent the reflection of the polished marble floors of the Codrington library at All Souls, Oxford and the Library at Trinity College Cambridge but also- more interestingly to create fractured, almost abstract compositions: for example, an open book on a window ledge in the library of the Society of Antiquaries, London, looking out towards the courtyard of Burlington House, or a book placed on a William Kent chair in a window embrasure at Houghton.

Of course, light the great destroyer of fine bindings, is the bête noir of militant modern conservators and hence taboo in most libraries. There is however a fundamental difference between reality and art- fact and fiction- even in the works of Damien Hirst and Tracy Emin. The day that conservation issues dictate to artists will spell the end of art.

EILEEN HARRIS APOLLO 2008

Smell the old leather and listen to the silence in these wonderfully evocative watercolours of great libraries by Hugh Buchanan.

RACHEL CAMPBELL JOHNSON Top Five Galleries THE TIMES Dec 2008

Libraries are generally rather dull places where nothing much happens apart from the odd snore or cough. But for Hugh Buchanan who has just painted more than thirty of the finest libraries in the land, they are theatres of excitement.

‘Just look at that’ he exclaims as we sit in an alcove of one of his favourite subjects – the Society of Antiquaries library in London, the oldest archaeological archive in Britain. He is pointing at an elastic band that has been crudely twisted round a book a couple of times to keep its cover on. ‘ you can tell so much about the person who did that – that they are lazy, casual, or in a hurry’ . Next he spots some black electric wires tangled under a table. ‘They would be great fun to paint’.

As Fun Boy Three pointed out, ‘it ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it’ and Mr Buchanan’s skill is in fusing the most humdrum objects- a piece of skirting board, the glazing bar of a window, even a 13amp plug with eloquence. His paintings evoke a sense of peaceful grandeur and timelessness.

Mr Buchanan is arguably the greatest watercolour painter working in Britain today, and his library series is his crowning glory. Although regarded as a conventional artist in as much as his medium is about as fashionable as lacemaking among today’s modern art establishment, he is in many ways a soul mate of that ultra modernist Rachel Whiteread. Her concerns- books and the traces left by passing cultures- are the same as his. ‘I feel passionate about our heritage which is greatly under threat at the moment’ he says ‘I’m always looking for new ways to interpret the past. Battered books are beautiful. They contain knowledge bit I also like their sculptural qualities, they are architectural shapes’.

His true focus is not however architecture, or even books, but light. Like a theatre director, he is constantly playing with its different effects: fingers of white morning light stretching across oak bookcases in the Society of Antiquaries Library; tiny chinks of light peeping through the closed shutters of a brown study at Houghton Hall; the dull luxuriant gloss on some fat Moroccan bindings at Eastnor Castle; the shimmering, almost aqueous light, of the marble floor in the library of Trinity College Cambridge. One of his best paintings is simply of two books on a leather desk, where the light is so dim and dusty that the volumes almost disappear.

CATHERINE MILNER in Country Life 2008

Hugh Buchanan achieves the seemingly impossible by making watercolour paintings with the scale and presence of oil paintings, without sacrificing any of the medium’s characteristic lightness and transparency. The monumental quality of his paintings comes partly from their size, but chiefly from their subject matter. Buchanan paints the interiors of great houses- shafts of pale sunlight falling across fluted pilasters and classical architraves, with perhaps a faded Chippendale chair in a corner. He has recently turned specifically to libraries, but rather than the surroundings it is the books themselves- sumptuous in teetering piles, or faded crumbling tomes held together with festoons of pink tape- that often take centre stage.

THE WEEK 2009

Light is important in these images and the watercolour medium favoured by Buchanan offers a way of conveying light which saturates in sepia, like the afternoon sun catching dust motes in its golden beam. Unfortunately, on the kind of day Aberdonians call ‘dreich’ with no help from the interior lights they did not look at their best. Buchanan is an Edinburgh college of Art graduate who has sought out libraries in universities, public buildings and stately homes and includes a new interior of the gothic-styled divinity library in Aberdeen. He has an eye for evocative detail- the back of an ornate chair, a diamond shaped grille, but there is something a little too mechanical about his rendition of shelves upon shelves of books.

He has conveyed the spirits of books in close-up studies : frayed bindings tied together with ribbon, scarps of paper marking the place of a previous reader, but these works are not included here. The majority of the paintings here evoke the kinds of libraries one sees in stately homes and formal buildings, identical bindings ordered to impress, which are still unopened 100years later: imposing but passionless, and even for the book lover oddly uninviting.

SUSAN MANSFIELD The Scotsman 2009